Harrow and Hillingdon Geological Society

La Brea Tar Pit

Home | Monthly Meetings | Field Trips | Exhibitions | Other Activities | Members Pages | Useful Links

Rancho La Brea Tar Pits Museum, Los Angeles, California.

Mike Cuming

Situated in the heart of downtown Los Angeles, the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits Museum is not just a museum but a museum inside a working lagerstätte. [Lagerstätten, (sing. Lagerstätte) are fossil assemblages, which are remarkable for either their diversity or quality of preservation and, sometimes, both. (Good examples include the Burgess Shale in Canada, Ediacara in Australia, Messel and Solnhofen in Germany, Lake Turkana in Kenya and Rancho La Brea in California.] It has thousands of animals that were trapped in tar seepages during the Pleistocene, which have been buried and preserved by stream sediments from the nearby hills. The numbers of fossils (and of individual species) is vast, allowing population studies to be undertaken.

The geology comprises Upper Miocene beds which have been contorted during the orogeny that formed the Western Cordilleras, allowing pockets of oil and tar to be trapped, which form the basis of the California oil industry, which flourished in Los Angeles in the past but is now centred in the Central Valley of California. Erosion has subsequently removed the cover from some pockets, allowing seepages to occur frequently. Only a very small depth of tar can trap an animal and stream sediment deposition then buries the remains.

Pit 91.

Pit 91, the most recent to be excavated is at a depth of 15-20feet (4.6-6.1m) and they have been digging up fossils in Hancock Park since well before 1915. It is estimated there is another 5-8 feet of fossil material in Pit 91. Digging is on a 3ft x 3ft grid 6 inches deep and fossils are identified as they are excavated. Between 2004 and 2007, 2,000 to 3,300 fossils per year were excavated. Prepared fossils are displayed in the Page Museum.

The process of entrapment.

Rancho La Brea has 40-50 feet (12.2-15.2m) of Wisconsonian alluvial sediments ranging in age from 40,000 to 9,000 years BP. Some remains were already buried in stream deposits before seepage occurred. Many of the bones of animals are incomplete. Lower limbs are more frequently preserved. There is evidence of scavenging during entrapment events. Remains are in a jumble due to trampling and there is evidence of pit wear. It is estimated that one event per decade would suffice to account for these deposits. Entrapment is still happening.

The Dire Wolf is probably the most common animal, with hundreds if not thousands found, allowing population studies. Another example with numerous remains is the North American Condor, entrapped through scavenging on those animals already trapped.Injuries are probably over-represented, one example being the tip of a sabre-tooth found embedded in a sabre-tooth bone.

The animals.

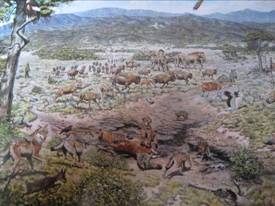

The range of animals represented include the horse, which subsequently became extinct in the Americas until re-introduced by Europeans, camels, ground sloths, peccaries, pronghorn antelope, badger, grey fox, black-tailed jack rabbit, striped and spotted skunks, gopher, long-tailed weasel, deer mouse, short-faced bear, the North American lion (rare), mammoth , bison plus lots of invertebrates, which are only now being examined and tar-dwelling bacteria. The bones are still bone and have not been mineralised. Interestingly there is one Mesozoic tar pit in Belgium, where 20 iguanodon were found in a coal mine.

Project 23.

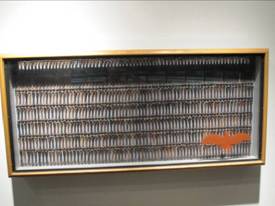

Work in Pit 91 is currently suspended, for at least 5 years, while the scientists work on Project 23. This arose when a new car park was being excavated for the Los Angeles Art Museum next door and another tar pit burial was found. 3 boxes of fossils have been excavated (hence the name of the project) and the museum has facilities to watch the scientists at work and notices of events, which include identifying the boxes being worked on and recent finds. Work goes on 7 days a week with 5 paid staff and several volunteers.

Sabre-tooth cat.

There are numerous examples of this cat (Smilodon californicus), of which there is one specimen in the Natural History Museum, probably originally from La Brea. It was very heavy at the front with heavy muscles attached to the first neck vertebra and enormously muscular front legs. Its jaws opened to over 90o and it had a large protruding sabre tooth with a serrated cutting edge. Some specimens show the tooth replacement between juvenile and adult stages. The sabre-tooth is a classic case of convergent evolution since this form has evolved several times. There is even an example of a sabre-toothed marsupial (Thylaco simulis). The sabre-tooth cat generally killed the young of large animals like elephants and sloths but there is still some dispute as to how it killed its prey.